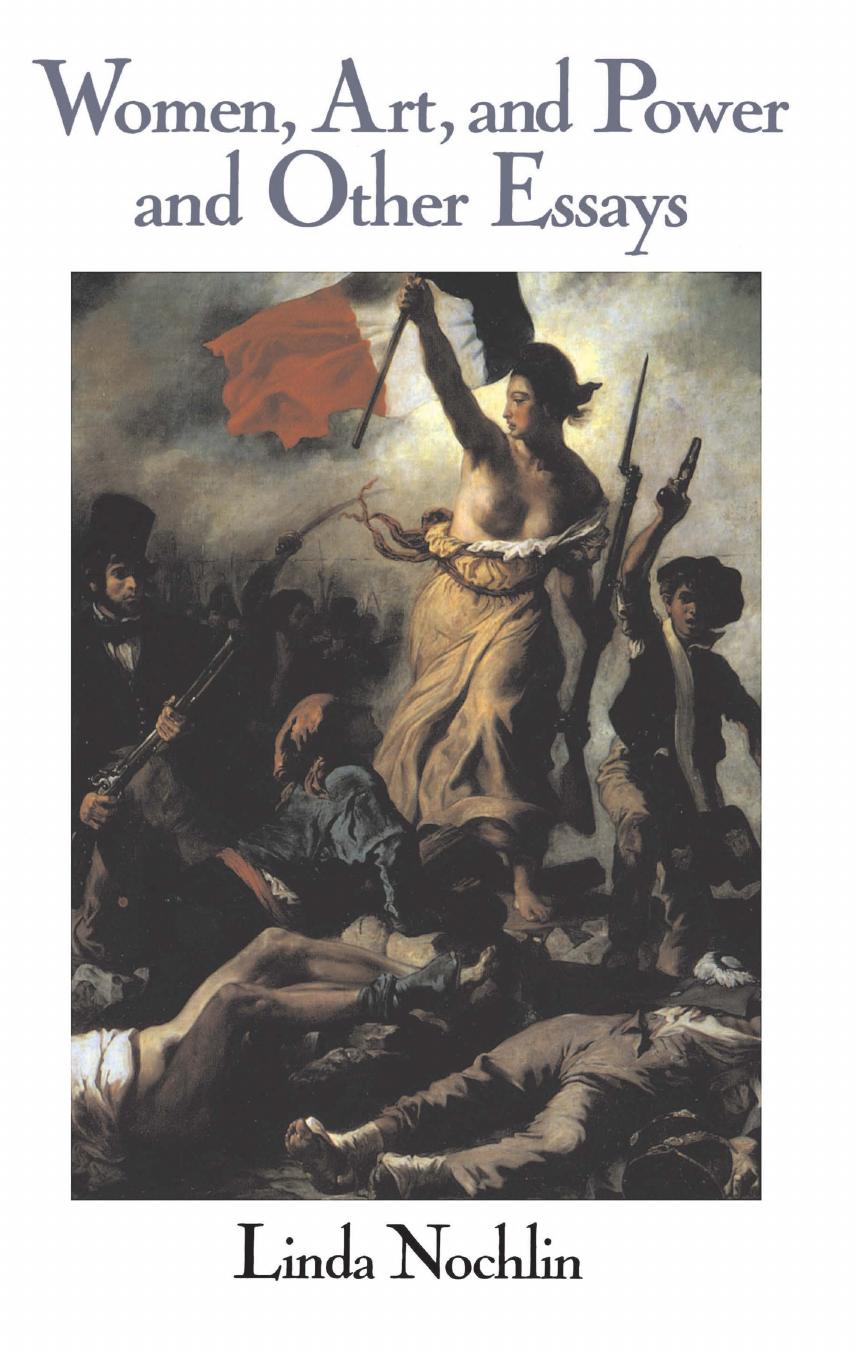

Women, Art, And Power And Other Essays by Linda Nochlin

Author:Linda Nochlin

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: Taylor & Francis (CAM)

2. Evocative Realism

What Cindy Nemser has called “the close-up vision”—“the urge to get up close, to zero in, to examine details and fragments”—has played a major role in the imagery of many contemporary women realists.2 This kind of realism is at a far remove from the social variety, with its emphasis on the concrete verities of setting and situation.

It was a woman artist, Georgia O’Keeffe, who first severed the minutely depicted object—shell, flower, skull, pelvis—from its moorings in a justifying space or setting, and freed it to exist, vastly magnified, as a surface manifestation of something other (and somehow deeper, both literally and figuratively) than its physical reality on the canvas. One can think of the work of O’Keeffe and of such contemporary painters of relatively large-scaled, centralized, upfront realistic images of fruit, flowers, or seed-pods as Buffie Johnson, Nancy Ellison, or Ruth Gray as “symbolic” in their realism as long as we are very explicit about the nature of the symbolism involved.

O’Keeffe’s Black Iris of 1927 like Ruth Gray’s iris in Midnight Flower of 1972, or Nancy Ellison’s cut pear in Opening of 1970, or Buffie Johnson’s Pomegranate of 1972, is a hallucinatingly accurate image of a plant form at the same time that it constitutes a striking natural symbol of the female genitalia or reproductive organs. The kind of symbolism implicit to these women’s imagery, O’Keeffe’s iris, for example, is radically different from that of more traditional symbolism, like the so-called hidden symbolism of the fifteenth-century Flemish realists.3 In the case of the latter, the depicted object—the “vehicle” of the pictorial metaphor, to borrow a term from literary criticism—refers to some abstract quality, shared by itself and the subject, or “tenor” of the metaphor, which it serves to convey. The irises in the vase in the foreground of Hugo van der Goes’s Portinari Altarpiece, far from being sexual symbols, refer to the future sorrow of the Virgin at the Passion of Christ. The significance may have been suggested by the notion of the swordshaped leaves of the flower “piercing the Virgin’s heart,” an implication made even more obvious in the name of the closely related gladiola, which is derived from the Latin word for sword. But the meaning of the flower is hardly visually self-evident. In the older work, the symbolic relation between the minutely rendered irises and the abstract suffering of the Virgin obviously depends on a shared context of meaning—the iconography of the Nativity: it is something the spectator is supposed to know, not something that strikes him or her the minute he or she sees the flower in its vase.

2. Georgia O’Keeffe. Black Iris

Download

Women, Art, And Power And Other Essays by Linda Nochlin.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18608)

Red Sparrow by Jason Matthews(5460)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3659)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3526)

Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy by Christopher Hart(3515)

Figure Drawing for Artists by Steve Huston(3434)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(3345)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(3292)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3161)

The Roots of Romanticism (Second Edition) by Berlin Isaiah Hardy Henry Gray John(2904)

Make Comics Like the Pros by Greg Pak(2903)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2874)

Draw-A-Saurus by James Silvani(2710)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2704)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2654)

On Photography by Susan Sontag(2622)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2574)

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday & Stephen Hanselman(2563)

Drawing and Painting Birds by Tim Wootton(2497)